We pull up outside the store and brood over as to why the search, in truth, leaves us shaken. Blessedly however, owner Quaid Johar is behind the counter under a gilt-framed picture of the High Priests exalted by the Bohras. As we walk into a sweet-tooth’s realm by choice, customers are flooding in. Someone wants rosogolla. Excitement jostles as young as childhood. It’s a glorious sight.

The journey of the Bombay Sweets is a story not just to decipher as saccharine, but as the outcome of foreign settlements in Ceylon in the early days. Among them were the Bohras, a unique amalgam of the Indo-Islamic community. A brief glimpse into their roots lead us to the Gujarati lexicon “vehvar” meaning ‘dealings’ or ‘honest dealings.’ This etymon seems tenable for the palate to have established their identity as ‘Vohra’, known as traders.

Hence, like most confectioneries that belong to the Bohras spewed across the globe, striving to serve quality products, the Bombay Sweet House (BSH) still runs as a family enterprise. Pioneered by Johar’s grandfather hailing from Gujarat, who saw a possibility of developing the business in Sri Lanka, having traversed as far as Africa and Europe, during the 30s, a shop with modest aspirations first sprung up in Hulftsdorp. It was after branching out to Kollupitiya from Keyser Street in Pettah, the store, named after its exotic items, saw an absolute sense of fruition gaining ‘landmark’ status and popularity like the modern GPS used nowadays.

“People would throng in multitudes, mostly school children,”

says Johar with aplomb. More to say, the classic musket, originally known as halwa, in 6 varieties is a favourite among Lankan migrants in Canada, UK and Australia. In fact, to settle with a single most popular item is not easy a task. Johar tells us the list is way too broad.

Sure enough, for their creed lies in the exquisiteness of flavours and texture that distinguishes one from the other. As a result, it’s hard to imagine, what now stands ensconced further away from a lace of other Indian sweet shops embellishing Wellawatte, is a small structure more like a take-away joint sweating to retain its once notable past. All that we gather from a calm employer such as Johar is a sour tale revealed quite ruefully. In its 55 years of existence at Kollupitiya, three months ago, BSH was asked to vacate without compensation. Still, for BSH, as a confectionary, sheer faith remains primal. Says Johar,

“you can’t have doubts,”

further adding in risk and rizq (provisions) for stability. To run a business whilst maintaining quality, needs utmost commitment, the kind his local employees lack.

“I need Indian workers,”

he goes on to admit rather tellingly. For this, a large hassle of immigration procedures awaits Johar should the urge turns urgent.

Moreover, for businesses like BSH, that have flourished over the years, exposure to harassment and stringent policies imposed by the Government as of recent, if continued, may lead to permanent shut down. “We didn’t have any legal authority to fight them,” he laments, with a valid but polite rebuke. The life of a Bohra beats according to the Islamic calendar than a Gregorian one. So, Johar shows us a placard announcing the shop’s closure for Ashura observed last week. How about the day before Eid? “Worse than a fish market!” he laughs, adding that Eid for him is just another day spent at the counter. Thereupon, reminiscing, a memory hard to erase is his father’s dedication for years: “He’d come home at 1 in the morning holding his fast having worked from 8 a.m.” Gazing at a glass of faluda thick with colours, compartments, and elements of merry is cathartic for an afternoon parching our senses. The sabja seeds are sodden deep in a snow of milk luridly crimsoned at the bottom and the ice-cream oh so cushiony.

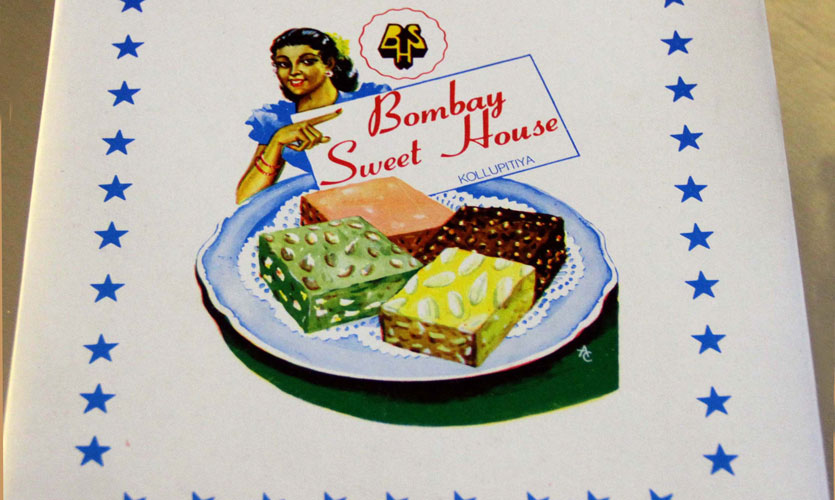

Certain delicacies, we are told, come down from Persia including the jalebi. Their packaging, whether for a kilo or ten, involves no charges, because customer, for BSH, is king. It would be sinful to have ignored the image bearing a woman, who, according to Johar should be 80 years old now, and as unlikely as it looks, the dish filled with musket is actually a boat at sea representing diasporic migration. Partly designed by his father, a misprint of the colours (blue and green) is why it’s hard to deduce this interesting concept.

Following a stock system recorded daily, BSH also adheres to wowing their customers given any occasion. But none of Johar’s sons plan to take over the business.

As we point out to have tasted the best gulab jamun in Shimla, Johar ends on a note far from cheerful:

“In another 15 years, mark my words, BSH will no longer operate.”

Then again, sweets symbolise good news, don’t they, we quickly retort at a smiling Johar, who assures BSH would offer better gulab jamuns some time soon.

photos Pradeep Dilrukshana

0 Reviews