Feb 04 2019.

views 1886The various micro aspects that merge to complete the formation of a human being are quite complex and advanced. From the DNA in our bodies to genes and other structures which are not visible to the naked eye, each one of them has many functions to keep us in control. Who you are physically and internally is determined by the expression of genes. Genes determine everything from your skin tone to the colour of your eyes and other features. But in some instances genes are not expressed. This was what motivated Iromi Wanigasuriya to explore what it takes for humans to be the way they are.

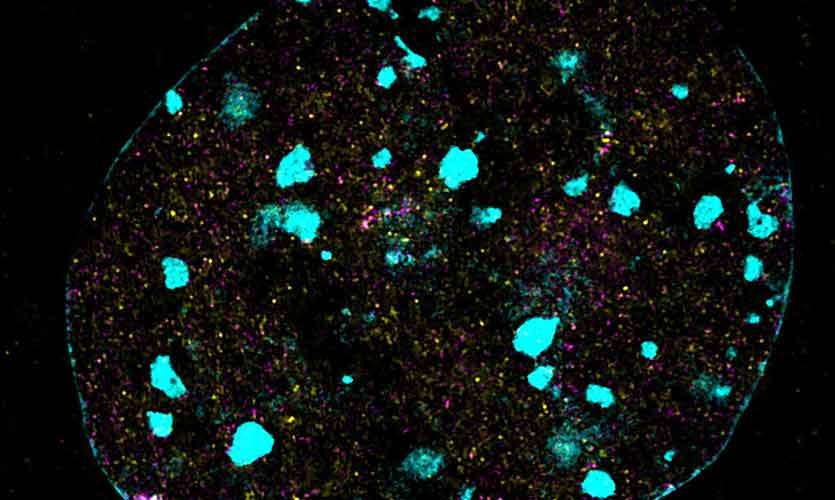

A proud alumnus of Devi Balika Vidyalaya, Iromi is currently a third year PhD student at Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research affiliated to the Department of Medical Biology at the University of Melbourne. Iromi’s research interest in epigenetics has motivated her to study the protein SMCHD 1 (Structural Maintenance of Chromosomes Flexible Hinge Domain Containing 1). With new imaging techniques such as airyscan, lattice light sheet and OMX R along with super-resolution techniques such as 3D SIM and dSTORM Iromi is investigating how SMCHD1 dynamics change in the cell in real time and how it interacts with other proteins to form a large DNA.

In a candid interview with W@W, Iromi spoke about her research in epigenetics and her observations on the field.

Excerpts :

Q: Tell us about you

A: I’m a third year PhD student at Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical research, which is affiliated with the department of Medical biology at the University of Melbourne. It is the oldest medical research institute in Australia, with over 100 years of history and a few Nobel prizes to its name. My PhD is in the field of Medicine, Dentistry and Health sciences and my research focus is on Epigenetics. I am particularly interested in an epigenetic modifier known as SMCHD1. Before pursuing my PhD I completed a Masters in Molecular Biology and an undergraduate degree in Science. I’m also a proud alumnus of Devi Balika Vidyalaya, Colombo 08.

Q: What inspired you to study gene expression?

A: I have been always interested in why and how we are the way we are and therefore wanted to learn more about it. Quite early on I realised that there was very little thought to us in a classroom setting. So I would immerse myself in trying to find answers in other ways. I came across a massive open online course (MOOC) platform called coursera.org. I took quite a few courses there. One of them, called ‘Epigenetic control of gene expression’, was conducted by the University of Melbourne. I was so interested I asked many questions in the discussion forums, as this was a quite a new area for me. The course conductor noticed my questions and she found my enthusiasm towards the subject refreshing. So we talked back and forth via email and now she is my PhD supervisor. That course is still running and I’m one of the teaching staff. So you could say that I have come a full circle.

Q: Tell us about your research in epigenetic control of gene expression.

A: Epigenetics is an additional layer of information on top of one’s genetics. We as humans have over 20,000 genes in every one of our cells at any given time, but not all of these genes are expressed in all cells. There are epigenetic modifiers that keep these genes either active or silenced so the cells can function the way they should. I study one of these epigenetic modifiers known as SMCHD1.

Q: What happens if epigenetic control doesn’t happen in the body?

A: It can lead to many diseases. For example, if something goes wrong with the epigenetic modifier that I’m interested in, it could lead to a form of muscular dystrophy called FSHD. One in 8,000 people around the world are affected by this. It could also lead to genetic defects such as Prader-Willi syndrome, which is an imprinting disorder, and a rare genetic disorder known as Arhinia where children are born without a nose.

Q: Does it happen through heredity or do external factors such as mutations also play a role?

A: Some, but not all, epigenetic modifiers can be transferred from one generation to another. Epigenetic process could be mediated by different regulators such as histone tail modifications, DNA methylations, differences in chromatin organization and other epigenetic transcription regulators.

Q: What are the practical challenges you have faced in carrying out this research?

A: I have been quite fortunate to be in an institute with so much advanced equipment to carry out my research the way I want to. Access to tools or expertise can be a practical challenge in many parts in the world. As exciting as research is, it is a very long process. And no matter how hard and accurate you work not all things work at all times. It’s difficult to explain this to someone from a non-scientific background, so it can be really lonely at times. To me this is one of the biggest challenges. Thankfully I’m in a really good lab with an incredibly supportive supervisor, so that helps!

Q: To what extent is research done on this field?

A: Although the concept of Epigenetics was formed about fifty years ago, it is still a rather ‘new’ field of interest compared to other research areas. So there’s still a lot to be uncovered. There is extensive research happening in all major institutes as it relates to every other aspect of biology and it is vastly important in terms of disease impact.

Q: Why should a country like Sri Lanka look at introducing more research opportunities for students?

A: I think Sri Lanka could benefit a lot from research. Not only primary research but also seeing a complete study through where the basic molecular mechanisms are understood and then that understanding is used in applications such as drug discovery. This could create a lot opportunities for the general public and contribute immensely to the economy. Creating opportunities and giving tools to future generations of students who can carry out such research will lay the foundation for such a future.

Q: Australia is a popular destination among Sri Lankans for various purposes including studies. What’s the procedure to apply for a PhD there?

A: Australia is a little different to other countries when it comes to PhD application process. You have to first find a supervisor in your field of interest before applying to the university. Your research starts from researching about potential supervisors. Doing a PhD is a huge commitment, so it’s really important to have the best support system you can, and your supervisor plays a primary role in it. Different people have different styles of supervising and wanting to be supervised. So talk to people working in the lab, figure out whether it’s the kind of place you will easily fit into. Once you figure out who you want to work with, you have to write to the person not only to express your interest in their research but also express who you are as a person. Keep in mind they have never met you, so it’s really important that you express yourself. While your academic merits are important for the university to process your application, who you are as a person, your ability to work in a team, and your ability to adapt is really important for a potential supervisor to decide whether you’d be a good candidate. Keep networking, be curious and ask questions: things happen when you make an effort to do so.

Q: Your message to girls aspiring to be researchers.

A: There’s a famous saying that the ship at the harbor is safe but that’s not what ships are built for. So step out of your comfort zone, be willing to take chances, ask questions! You can do anything if you set your mind to do it. Just like the ocean, your possibilities are endless; don’t be afraid to sail!

0 Comments