May 22 2020.

views 702Over the course of the years, Sri Lanka has seen many wars and insurrections, natural disasters and the spread of numerous infectious diseases. Sri Lanka’s silent generation, especially, have been exposed to many crises. Raised during a period of war and economic depression, they have lived through World War 2 (WW2) in British Ceylon from 1931-1945, the JVP insurrections, and most recently the Sri Lanka Civil War which occurred in 1983. We spoke to a few individuals who were young children during WW2 and asked them how they remembered that period. Their narrations, tinted with hues of childhood innocence, imply the importance of familial bonds and friendships in surviving periods of turmoil and uncertainty with one's childhood intact.

Deshabandu Jezima Ismail

The air raids at the time required that Ismail and her family return to her hometown in Ampara. “The schools were closed and the nuns went off to other parts of the country. We did not have any technology, but somehow the studies went on at home, supervised by the parents. I never felt the impact - that missing so many months of study affected our work. Very carefully and systematically the work was taken up and completed with the help of parents”. Ismail recalls that the period isn't one that was incredibly stressful, at least for her. “I can’t remember any kind of agitation and wondering ‘how are we going to do this’ or ‘how are we going to do that’. Things went on normally. But of course, it was not all fun”. She added that there were also many blackouts, and the blackouts were quite frightening for young children. “During the air raids when the planes flew over, we were scared of the bombings. At these times, when we had to draw our curtains and switch off the lights, it wasn’t funny, but it was almost like an adventure”.

“Studies wise, when we resumed our education and went back to school, the gap was really bridged by the teachers in the school. Somehow it didn’t impact negatively on the progress. I think if I was a teacher or principal during the current COVID crisis, I would have been really stressed out, what with all the Zoom classes and all that, wondering how we could get the processed sorted out. But also unlike then when we did not have such advancements, the current lockdown has made the children very addicted to computers as they are spending more time on it for various reasons. That is bothering me. I come from a generation that didn’t grow up with technology”. Connecting her experiences between the periods of uncertainty and stress back then and now she shared “We happen to be daughters of an engineer, who was a government servant and he was in government bungalows and everything had to be relocated, but we found places outside Colombo and there were enough space and sufficient processes to deal with the crisis. But it didn’t depersonalise our lives. But unlike now, there was no social distancing and we were able to catch up with people, the transport wasn’t hindered, politically also we had statesmen who really knew what was required for the people. On the day of the Japanese air raid, we were shopping. I even remembered the toy I bought - it was of Japanese make, a little Donald Duck on a bicycle, and after the raids, I felt like throwing it away. We had to come home as a blackout was declared. There was no outright terror, but nervousness which did not lead to fear”.

Nizam Cader

Cader shared that during the war, he lived in Galle Fort, but had to relocate to Bandarawela for safety reasons. “They were expecting Japanese attacks, so everyone in Galle Fort was evacuated. One of the most memorable things about Bandarawela was that over there, we used to buy durian for 3 cents and 5 cents!”. Speaking about his education, he explained “I was at S. Thomas’ but we had to move. S. Thomas opened a branch in Peradeniya where they had a half-day of school for us, and half-day for Kingswood. After some time we moved again and this time we studied at St Paul’s Milagiriya. Even here it was half-day for them and half-day for us”. “Since we were in Bandarawela, it wasn’t that bad,” Cader remembers. “The only thing was that food was quite difficult to get as they were made available only 3 times a week and there were rice rations and such.” He also recalls that while travelling to school by train, he noticed the slogans plastered all over that said ‘To stay at home is common sense, the trains are needed for your defense’. This was because the trains were already quite crowded and the soldiers from many countries used to travel by plane as well.”

Benedict Rodrigo and Rita Ruby Jayamanne

Speaking on behalf of her grandparents, Ludmila Bopitya remarked “My grandmother and grandfather both lived through WW2. Grandma used to say that she was in the Sunday service when the Japanese bombed Ceylon. They had taken shelter in the church and all the children were asked to put the clips of their pens or break the pencils and put in their ears to protect them from the loud noise of bombs''. “I also remember her telling me about how some of the Japanese air crafts crashed into the Muturajawela Marsh and how most of them were dead and burnt while one survivor was caught and a villager has given him shelter although later on the village head (My great grandfather) had to inform about this to the British. “My grandfather from Uswetakeiyawa was a young lad during the time (He’s 94 now), and they have a song that they used to sing about this incident. He used to sing it to me and I can remember it by heart”. Ludmila adds that there’s so much more she would like to know of that time, and hopes to learn more about what he remembers. “My grandfather said that they were asked to dig the ground in the shape of a W and whenever there were air crafts flying above, they used to run and stay inside tunnel-like holes. I don’t know the reason for the W shape. He too cannot articulate why”.

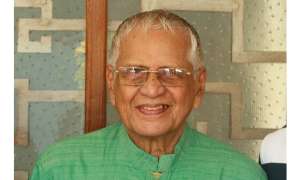

M. Wijeratne

Wijeratne, who was born in 1932 explained that he “was going to school at that time, and used to read the papers, so I had quite a bit of knowledge about what was going on”. Born in Pelmadulla, he shared that they owned 2 houses, one of which was periodically given out to be used by various individuals who needed a safe place to stay. “My father sent me to study at St. Aloysius College during the war. Since it was a Catholic school, it was headed by an Italian Priest. I recall that I was at school when the war ended, and how the priest gathered to give us a speech about the good times to come. Back then” Wijeratne adds as an afterthought, “we had SSCs (Senior School Certificate) instead of OLs, and that was enough to gain entry into the university”. Although the war had ended, Wijeratne explains that it took some time for things to get back to normal. “And rice, for example, was imported and people did have some difficulty obtaining rations”.

Maria Anthony

Despite her failing memory, Anthony, who was quite young when the war took place, fondly recalls how she used to play with her friends on the streets as foreign armies rode by. “They used to throw various food items for us to catch, which included cans of some of the tastiest fish I have ever eaten”. She claims that for this very reason, she and her friends used to look forward to seeing the forces drive by. However, she adds that as she was quite young, she did not really understand the seriousness of the war and that the blackouts and having to hide in trenches when air raids were announced, were quite exciting.

0 Comments