Sep 03 2020.

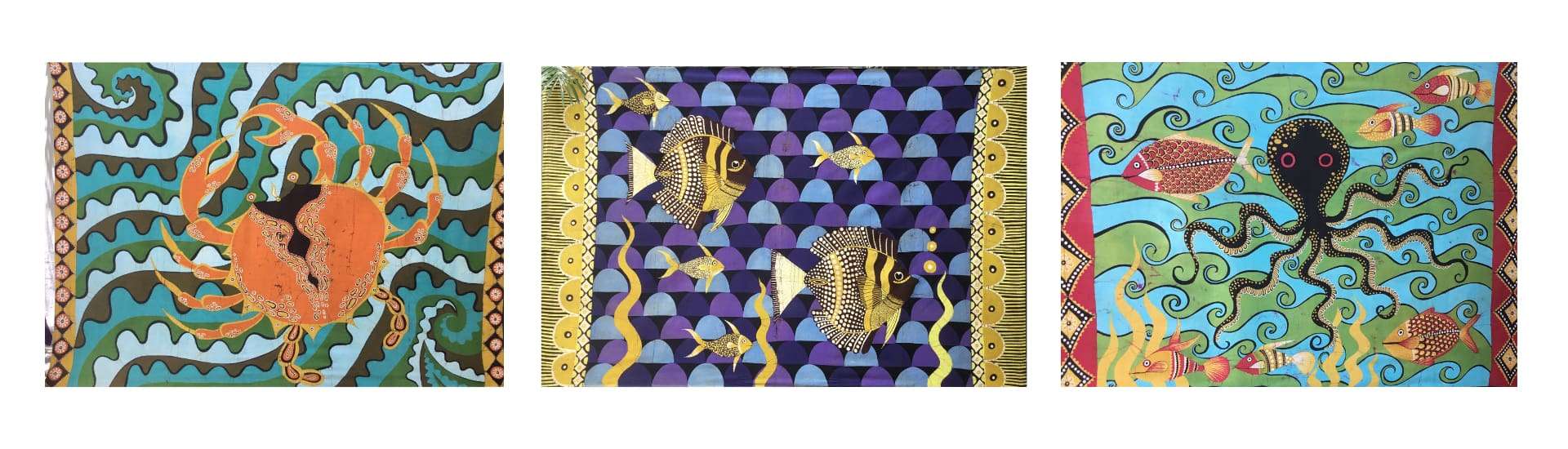

views 1575There was a time when Sri Lanka’s batik masterpieces were a global hit. From wrap-around skirts to blouses and many other outfits, the industry certainly flourished. But the introduction of the open market economy took a heavy toll on local industries including batiks. Several decades later, the Gotabhaya Rajapaksa regime has now allocated a separate ministry to revive the dying industry and many local artisans feel that the time has come to set things right. From empowering local batik manufacturers to introducing Sri Lanka as a hub for batiks and local industries to introducing batik garments in hospitality-related ventures the incumbent regime certainly has various options to bring the industry back to its former glory.

“Back in the 1970s, the Sri Lankan batik industry boomed,” recalled Senaka De Silva, veteran fashion designer and choreographer in an interview with the Daily Mirror Life. “I remember doing many sarees for Mrs Bandaranaike as well and we participated in many overseas trade fairs. But many of these outfits didn’t have a fashion sense. Therefore back in 1973 Kem Martenstyn, a fashion icon and designer par excellence opened ‘Orientations’ a shop dedicated for batik-inspired upmarket, wearable fashion garments. These included blouses, wrap-around skirts which were in vogue at the time.”

“We did a presentation in Paris as we were the feature country,” Maeve Martenstyn recalled about an era when the Sri Lankan batik industry had a huge demand overseas. “So we advertised the country through clothes. Following that we were invited to Amsterdam for their water sports festival. They were trying to promote Sri Lanka as a destination for water sports and therefore we designed batik-inspired beachwear and resort wear.”

It was afterwards that Senaka had started working at Orientations since they were exporting a lot of garments. “We were into hand-embroidered garments, cutwork embroidery and beeralu-lace among others,” Martenstyn continued. “We also took part in trade fairs around the world from Berlin to Copenhagen, New York and we even had a shop at Regent Street in London at the Sri Lankan Tea Centre! However, we had a lot of issues during the 1983 riots and subsequently closed down the shop during the late 80s. But five years ago I did a show in Spain.”

At the time Sri Lanka produced all raw materials required for batiks. “We had Thulhiriya, Veytex, Thultex, Pugoda and many other textile manufacturing companies,” Senaka added. “They were making poplin and the nuns were producing high-quality silks. Likewise, the most important materials for fabrics were produced locally. There was a government shop called Jana Salu, selling all silk materials which was located opposite Oberoi and there was another shop at Ratmalana. All dyes were imported from Germany and the prices were getting more and more expensive. However, the government didn’t look after the industry. With the open economy, people started producing garments in factories and fabrics got cheaper and eventually, local producers closed down. Thereafter they started selling cheaper poplin, silk and even screen-printed batiks.”

Back then a metre of silk had been just Rs. 180 but today it costs Rs. 2500. “Most batik sarees which are available in the market are screen-printed in India. Likewise, they are underestimating the value of local artisans. Countries like Indonesia produce their own dyes. The government could have brought in cheaper dyes from Malaysia. But when it was in a dying trend there were rebellious characters such as Ena De Silva, Eric Suriyasena and Buddhi Keerthisena who revived the industry. Special credit should go to Ena for reviving the industry along with Geoffrey Bawa,” Senaka added.

The Ena De Silva legacy

Acknowledged as the ‘rebel who changed the course of batik in Sri Lanka’ Ena De Silva is credited for reviving the once-dormant industry. Along with her dear friend Geoffrey Bawa, De Silva was able to introduce batik tapestries to many prominent buildings designed by architect extraordinaire Bawa including the Bentota Beach Hotel and the Sri Lanka Parliament. Ena returned to Matale, her hometown back in the 1980s and established the Matale Heritage Centre and trained the community in various arts and crafts. These included everything from carpentry to wood carving, abstract hand painting, brass foundry and batik tie-dye. Several decades later this Centre is one of few that continues to empower local artisans while attracting many visitors from all parts of the world to admire Ena’s contribution to her native place.

Buddhi Keerthisena – pioneer of a household batik label

Buddhi Batiks was first established in the 1960s and batik was limited to decorative items and outfits such as sarongs, kaftans, kurtas etc. After participating in many trade fairs and familiarising the concept the industry boomed until 1983. After the riots, the tourism industry dropped and the batik industry took a plunge. Thereafter Dr Buddhi Keerthisena was able to revive it by catering to the local market. For this task, he designed customised outfits for well-known celebrities who in turn encouraged Sri Lankans to wear batiks. His legacy is being taken forward by his daughter Darshi Keerthisena.

Modern batik wear introduced by Eric Suriyasena

Eric Suriyasena is one of the leading batik connoisseurs in the country. For over a century he has taken the ancient craft of dyeing on cloth using a wax-resist method. He was also instrumental in pioneering batik as a medium of fine art and an elegant fashion statement. He believes that batik needs to be kept alive as it has been part of our heritage. Mr Suriyasena continues to make batik an art which is accessible and enjoyable while engaging audiences across the globe.

0 Comments