Jun 13 2020.

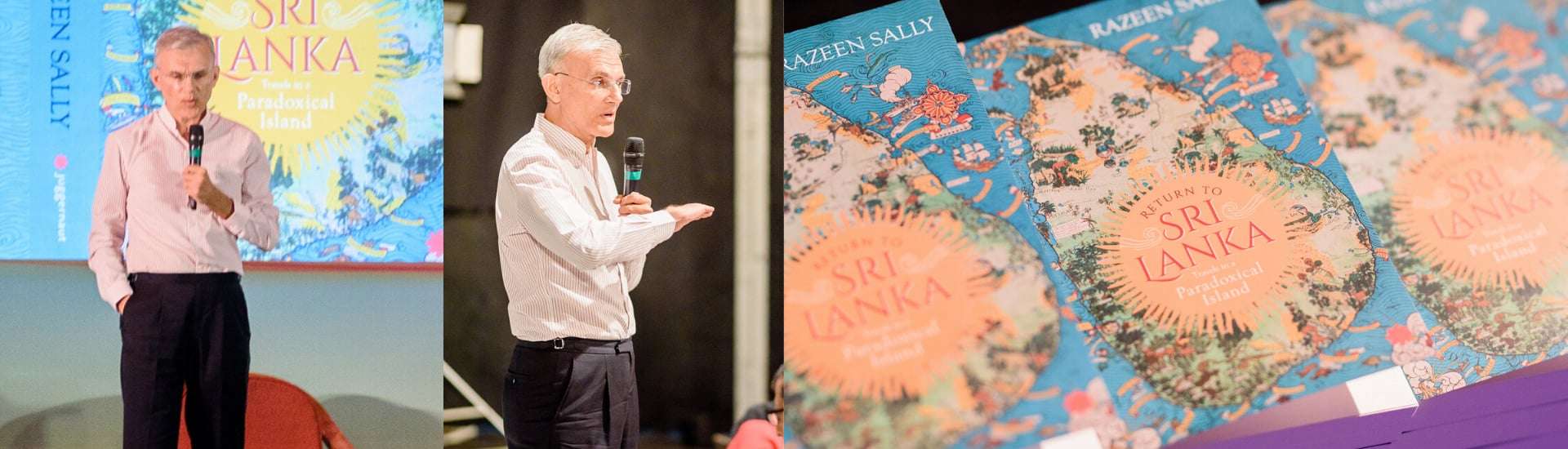

views 841Professor Razeen Sally's travel memoir "Return to Sri Lanka: Travels in a Paradoxical Island" is a labour of love; a far cry from the many books and articles he has authored on trade policy. Having spent most of his life outside Sri Lanka, and born to a Sri Lankan father and Welsh mother, Sally is a "'half-half' Sri Lankan: half insider, half outsider". Depicting consonance with his birth country, Sally's book is tinted with hues of his personal experience, and the process of putting it together, a "voyage of self-discovery". The book delves into his personal story beautifully interwoven with his travel story and takes the reader through the country and its many paradoxes. Below are excerpts of the email interview with Sally.

You have lived a very eventful life. Tell me about it.

My father is Sri Lankan Muslim, Badulla born and bred. My mother is British, from North Wales. They met on a ship in 1955; my mother came to Ceylon to marry and settle down in 1961. So I am a “half-half” Sri Lankan: half insider, half outsider. I was born in Colombo in 1965 and spent my childhood there up to the age of thirteen. My childhood was set in 1970s’ Sri Lanka, revolving around Colombo, Mount Lavinia (my father ran the Mount Lavinia Hotel), and Ratmalana (where we lived). It was a time of political and family turbulence, especially because my father was arrested, remanded, and jailed. We left Sri Lanka in late 1977. I came back infrequently over the next three decades: Sri Lanka receded from my mind and world. Since 2009, I have been back frequently, several times a year, spending time in Colombo and travelling all over the island. I have lived in Singapore since 2012, teaching at the National University of Singapore. Between 2015 and 2018, I was an adviser to Ranil Wickremesinghe’s government and chaired the board of the Institute of Policy Studies. But my governing passion in the last decade has been my rediscovery of Sri Lanka and writing a book about it.

You are an academic with specialisation in Trade Policy. Why did you choose to write a book about Sri Lanka, and a travel memoir at that?

The idea of writing a book about Sri Lanka germinated soon after my first return visit in December 2006. After decades of absence and forgetting, Sri Lanka started to pull me back. I began to yearn for reconnection with the land of my childhood. I wanted to revisit my childhood – the places and people I knew long ago – but also see the country afresh – to rediscover it. My childhood world was limited to my Muslim extended family and my father’s circle of friends, and to Colombo and a handful of outstation bubbles. I had so much more of Sri Lanka to discover. A book project, I realised, would be the most thorough way to go about it. With writing in mind, I would travel seriously, with a purpose: do my research on history, culture, religions, politics and the economy; seek out people and listen to their stories; travel with alert senses; take copious notes, and reflect deeply when putting pen to paper. Early on, I also realised I didn’t want to write an academic or policy book on Sri Lanka. Others had done that, and I wasn’t an academic expert on the country. Besides, I had been an academic for decades and was getting bored with that kind of writing. I wanted to write about Sri Lanka differently, ranging more widely and conveying much more than I could as an academic or policy wonk. I wanted to write about Sri Lanka as a writer, not as a professor.

What was the process of working on this book?

The book is labelled a “travel memoir”. These two words furnish the book’s composite frame. The “memoir” is my personal story: childhood, absence, and return. The “travel” is the journeys I did, starting in 2009: mostly long road trips, sometimes two or three a year, that crisscrossed the island, west, south, east, north, and middle. My travel-writing compass was an extensive reading of travel literature over a quarter-century. Classic travel books – travel writing as great literature – use the medium of the journey to capture something bigger and transcendent, a spirit of time and place. My travel-writing pantheon includes Bruce Chatwin, V.S. Naipaul, Patrick Leigh Fermor, and, from an earlier generation, Robert Byron and Evelyn Waugh. I had long wanted to write a travel book. Sri Lanka was the obvious place to start.

This was my mental atmosphere for book writing. I used my memoir and journeys to address the big, broad themes of Sri Lanka’s history, culture, religions and current affairs, and to capture, as best I could, a spirit of time and place, especially Sri Lanka in the decade after the end of its civil war.

For me, the writing process was completely new. I did my desk research, went on my road trips, talked to lots of people in Colombo and outstation, and wrote in fits and starts. Trying to write like a writer and not like a professor was really hard. Even before I had tried to unlearn bad academic habits and write clearly and crisply, like a good journalist. George Orwell, V.S. Naipaul, and Evelyn Waugh were among my literary models for unsentimental, concise, cut-glass writing, so different from the South Asian norm of long, luxuriant sentences and abundant sentimentality. But now I had to prune the dry blackboard analysis of the professor and write in a much more personal voice. I had to be more descriptive and vivid about people, encounters, and landscapes, and be sensitive to storytelling, modulation, and pace. I had to think hard about using memoir and travel to illuminate bigger Sri Lankan themes; concretely, my challenge was to match passages of personal narrative with excursions into history and current affairs to create a seamless effect, a smooth flow, and avoid a disjointed one.

This was a laborious, extended process of trial and error. I write slowly, as a rule, agonising over words and sentences. Now writing became even slower. The book went through three drafts over eight years. I had the godsend of a brilliant editor, Supriya Nair in Bombay, who told me exactly what was wrong with the draft I sent her – bad structure, conflicting objectives, too much professorial writing and not enough writer’s writing, lacking a personal voice – and gave me just the right remedial suggestions. It took me a year and a half to finish the final draft. Having gone through this rite of passage from academic to literary writing, I’ve caught the bug – travel writing in particular – and am not sure I can go back to the straightjacket of academic writing. Mine has been a discovery of language, of using language to convey what I saw, felt, and perceived; in short, of language as a way of seeing more deeply.

What was one of the most surprising things you learned in writing your book?

My rediscovery of Sri Lanka yielded many surprises. The best were serendipitous. “Serendipity” – chance events and encounters that happen in a happy or beneficial way – comes from Serendib, the name Arab traders gave Sri Lanka. Travel and travel writing are voyages of self-discovery. And self-discovery has been my biggest surprise. I discovered how strongly Sri Lanka pulled me back and drew me in after a long absence – much more than I expected. I discovered my love for it, warts and all. I discovered a special love for its back-of-beyond places in all their stunning, wondrous variety of people, fauna, landscapes, and coastlines. I can’t think of anywhere else of comparable size that can rival Sri Lanka in this regard. These are places of calm and silence, peace, and contentment. Most surprising, rediscovering Sri Lanka turned out to be a part of a new spiritual journey, into Vipassana meditation and its connection with original Buddhism. Travelling in an ancient cradle of Buddhism, especially its remote village temples and forest hermitages, some long-abandoned to the jungle, gave this spiritual journey essential context.

What inspired you?

My Sri Lankan road trips – the longer, more circuitous and varied the better – always gave me a special thrill. The journeys, the way stations, my encounters with people and places, especially off the beaten track, never failed to inspire me.

Threaded through the book are pen-portraits of people who inspired me in their different ways. The Colombo chapter has a long section on my favourite “Colombo characters”. The following travel chapters describe encounters with people who left a special impression on me. Together they form a Sri Lankan kaleidoscope: humanitarians living a life of practical service for the poor and vulnerable; deeply spiritual men and women of different religions; resilient women who bear the burden of useless menfolk in the family and workplace; professionals and activists who speak truth to power, expose wrongdoing and strive to improve Sri Lanka’s rotten public life; entrepreneurs who create wealth, sustain livelihoods and care about their country at the same time; village guides on my back-of-beyond treks with their soft, gentle ways and love of nature. These characters redeem Sri Lanka for me. They rise above the mire – the cruelty, corruption, degraded institutions, chauvinism, ethnic strife, lackadaisicalness, and complacency – to show the better face of Sri Lanka. They radiate wholesome qualities that reveal that only some men are vile. They are Sri Lanka’s hope for a better future.

What do you want readers to take away from the book?

I’d like readers to take away a nuanced, variegated understanding of Sri Lanka, but love it at the same time. Sri Lanka is complex and multi-layered, a light-and-dark, heaven-and-hell country convulsed and consumed by its own contradictions. It makes the island frustrating, often spilling into despair, but also fascinating and bewitching. It is stuffed full of puzzling paradoxes. I try to make sense of these paradoxes, starting with Sri Lanka’s combination of incredible charm -- tourists and expats fall head over heels for Sinhala Buddhist culture in particular – and an astonishing record of violence that goes back to ancient times. Another paradox is Sri Lanka’s extraordinary religious and cultural hybridity, and the backlash against it from Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism, but also from the minorities. Sri Lanka looks outward – to other ethnicities and religions, and to the sea and the world beyond; but also inward – to exclusive and excluding races and religions and the myths that sustain them.

But my book tries to tug at readers’ emotions, not only their intellects. I want them to come to love Sri Lanka if they are new to it, or deepen that love if it already exists, despite the country’s many dark sides. I want them to venture out of Colombo and outstation bubbles to myriad back-of-beyond places where they will experience a different Sri Lanka. I want them to be awed and inspired by the island’s unique natural cornucopia. And to encounter some of those Sri Lankans, with their spontaneous grace, warmth, and hospitality, who show the country’s better human face.

In Sri Lanka, the book is available at Barefoot, M.D. Gunasena, Vijitha Yapa and other bookshops at Rs 1750, and can be ordered from pererahussein.com, with delivery to your door, at the same price. Internationally, it is available at Amazon and other digital sites, and on the publisher's website at juggernaut.in.

0 Comments