Sep 15 2022.

views 496

“We the Kalladi Village people (at Verugal) lost our traditional heritage over the past few years. For instance, the history of the Festival at Kalladi Sri Neeliyammam Kovil and the places where our traditional temples are situated cannot be known by our younger generations since it is forbidden.” This is an excerpt from a message by people of the Palankudi community penned at the ‘Memories from the Margin’ exhibition that concluded recently.

‘Memories from the Margin’ was a project by the Social Cohesion Thematic by the Centre for Poverty Analysis funded by the Think Tank Capacity Building grant implemented by the University of South Carolina Rule of Law Collaborative. “The project was a call to include voices from the margins in the reconciliation narrative. We worked with a group of 25 youth from Verugal and Santhosapuram off Trincomalee on the East Coast. They were trained as co-researchers and the exercise was to bring out the narrative history and the post-war experience of the Palankudi community. We did an initial scoping and on the second visit we trained them with disposable cameras, the research ethics and how to conduct interviews,” said Thamindri Melissa Aluvihare, Senior Research Professional at CEPA.

Even though the project focused on bringing out issues in the post-war context the community had been more keen on preserving their history which was slowly getting erased away. Santhosapuram and Verugal are two border villages which were located in close proximity but the Palankudi community was later displaced and was resettled. The Community had suffered immensely at the height of the war. Speaking further, Senior Research Professional Natasha Palansuriya said that the 25 youth were then put in groups and given cameras and the idea was that they take a picture that would bring out a story that relates to their Palankudi identity and history and also brings out a story about how things have affected them in the post-war period. So what they did was they went through the images, spoke to the village elders and got information from them.”

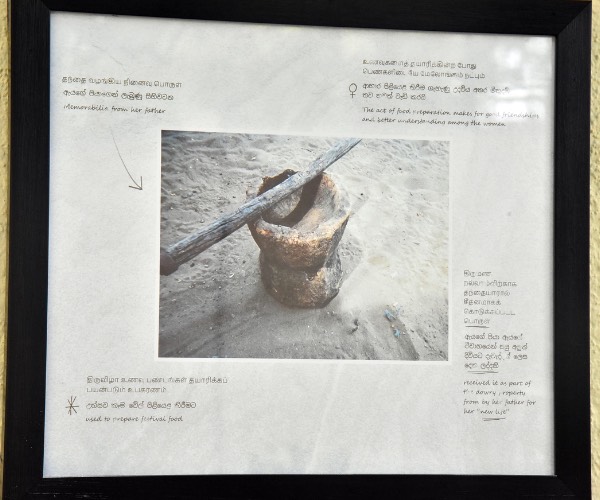

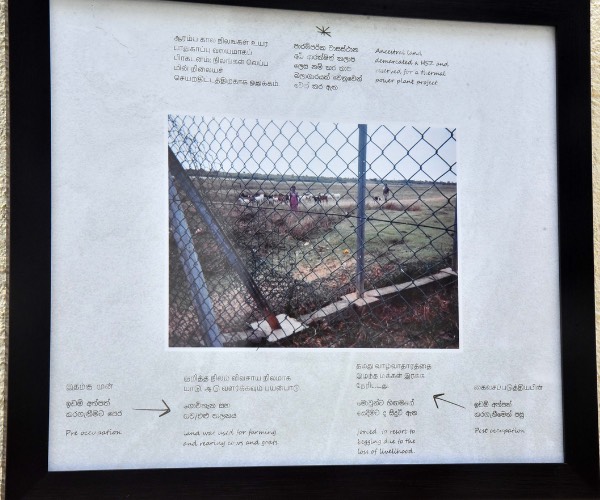

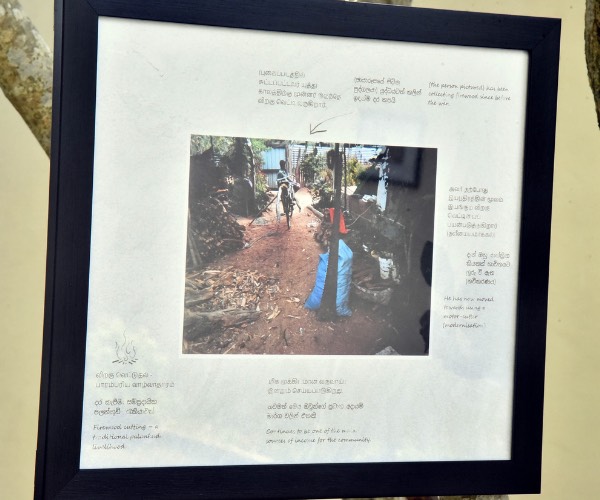

The images detailed various issues that they face from livelihoods to poverty, assimilation, erasure of culture, and scarcity of water to militarisation and were mounted in a way that brought out the concept of margins as means of prompting viewers to look at the narrative. “Most of these stories arise from the fact that they have not been identified – that they haven’t had the legal and institutional recognition as the Palankudi people. While the narrative was birthed from the community itself, the researchers have then triangulated the research and given conceptual definitions and the academic background to it. For example, in places where they spoke about Buddhistisation and militarisation, we would include the term militarisation even if they were talking about it in effect,” Aluvihare added.

The impacts of assimilation were highlighted through these images portraying how the current culture is erasing since they have assimilated to the dominant Hindu culture in the area. “Assimilation eventually leads to erasure and even the language has been erased over the generations. People who speak their language are way over the age of 80 and not mobile enough for us to preserve the language. The identity issue also compounds other social issues as well. For instance, they have the traditional knowledge to carry out indigenous methods of farming, foraging and agriculture but they are not permitted to do that because they are not recognised as indigenous people by the Forest Department. Those who have access to it aren’t doing their job properly and it eventually leads to deforestation,” Palansuriya continued.

“In Santhosapuram they don’t have access to water and as a result, their hygiene is compromised. When children go to school they are perceived as low-caste and dirty. In society, there’s a perception that the Palankudi community is the lowest caste of Hindu society. Therefore, children drop out of school and for generations, the cycle continues. For example, economy and social growth have been hindered – it is only now that they are having conversations about the importance of having political representation, the importance of organising themselves within society and these factors cater to the fact that they have systematically been kept away from education due to the lack of access to water and other issues. even to lobby for what they are going through they don’t know whom to speak to because they were unaware of their rights. Our project coincided with their timeline, revitalising their conversation quite unintentionally.”

Another excerpt from their messages reads as follows; “The indigenous people should be recognised and indicated in law books as ‘Palankudi’, ‘Mootha Kudi’ or ‘Aadhikudi’ which are honourable names of indigenous people.” “One of the issues is that over the years, Palankudi has become a derogatory term and therefore, identifying as the Palankudi community has become derogatory. “As a first thing what they told us was that they didn’t want to be identified with this term. They gave us two words, Palankudi and Aadhikudi – Palankudi means oldest community and Aadhikudi means first community but they use Palankudi more regularly. The stigma comes with assimilation since they have been assimilated as the lowest cast,” Aluvihare explained further.

Once the team identified their story, the initial research methodology was amended so that it brings out the spirit of the community. In fact, it was more important for the people to preserve their history. The village comprised more women than men since the men have been victims of the war. Many were missing, disappeared or dead. The researchers believe that they have laid the foundation to take this project forward and see that this community is granted the rights exercised by every other citizen on this land.

0 Comments