Nov 07 2022.

views 1122

Rukada Natya or traditional String Puppet Drama, commonly known as puppetry was one kind of entertainment that kept audiences glued to the stage with performances that were often based on satire and humour. Although local Rukada Natya originated from the southern coast of Sri Lanka, particularly from Ambalangoda and Balapitiya, the origins of contemporary Rukada plays can be traced back to the Nadagam tradition or Folk opera. The purpose of Rukada Natya was to bring communities together, teach moral lessons as most plays were based on Jataka stories, enjoy humbling humour and reflect on past influences of domestic society. However, today, Rukada has been classified as an art form at risk, on the brink of extinction.

In 2018, Rukada was added to the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. The most popular puppeteers are members of the Gamvari family who have been continuing the art form for four generations. However, today, they have to make compromises to the costumes and characters due to financial issues. Back in the day, a travelling troupe of puppeteers would carry with them around 50-200 puppets. But this number has been reduced to 20-30 puppets today.

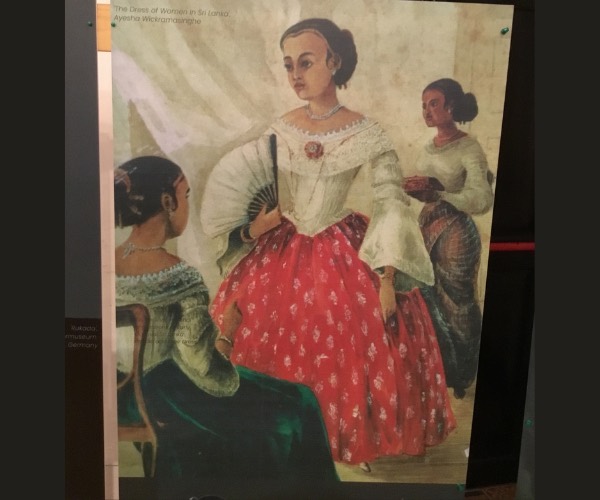

The female characters found in Rukada plays vary from royalty, nobility, common village folk, mythical characters to dancers. “In this work we have looked at trying to re-gender the space and place of women in history during the Kandyan period through the puppets,” said Sulakshana De Mel, Manager, Museums at Collective for Historical Dialogue and Memory at ‘Costumes Speak’ an exhibition that reflected on the history of Sri Lanka through puppet costumes.

“It’s a juxtaposition of a Kumarihami and a Kabakuruthuwa. You find Kumarihami in the Ehelepola saga play and it’s heavily embroidered. However, Rukada of Kumarihami found in the Munich theatre museum is actually clad in a somana. You find embroidery in their work and interestingly if you look at the different historical sources, the Kumarihami’s clothes in the Kandyan period are similar to Queen Dona Catherina and I’m trying to find out why they modelled their clothes on a queen who lived a few centuries earlier than the Kandyan period”.

However, the juxtaposition of the attire of coastal women wearing the long-sleeved jackets is that it has three different lace work. A jacket design inspired by beeralu weaving was mounted on a dummy. Interestingly, the puppeteers are of the view that women are not supposed to touch the clothes and traditionally, to date, it’s the men who stitch clothes based on reasons of purity and pollution. They say that it had continued since the time of their ancestors due to a caste issue. “Puppeteers belong to a different cast to the ones who make the jacket. This is very symbolic of a particular coastal cast group. When the Rukada have 3-4 plays they have women clad in this jacket and they get the women from that particular caste. This is the only point historically where the women are stitching this jacket for the Rukada makers,” De Mel further said.

King Sri Wickrama Rajasinhe is one of the main characters in the Ehelepola Saga play and the Nadagama which was performed at Charles Henry De Soysa’s Bagatalle House before Prince Alfred, back in 1870. Over the years, the evolution of King Sri Wickrama Rajasinghe Rukada with different choices of fabric, embroidery work and colour of shoes reveal multiple layers of politics, trade and social practices. “But in the collection at the Munich museum it’s not only Brownrigg and John Doyle who are in British uniforms, but Rajasinghe and the Vedi Raja too are in British uniforms,” she added.

In Rukada plays, the bahubuthaya or the sellanlama/pulle comes first. This is the jester and is used for satire and speaks about issues in a village that you can’t directly talk about. “When I asked about the history of the character from the puppeteers, what they have heard from their elders is that it’s an Indian merchant who got stranded in Ceylon after a shipwreck off the Jaffna coast. Interestingly this character comes from the earlier Tamil nadagam tradition. You can well trace through this character the nadagam tradition in present-day Rukada. There was another character that also came in the 1920-1940s called the sellamlama but present-day puppeteers don’t know how to make it anymore because the dancing steps of that puppet are very much into the nadagam tradition.”

The research also explores who the weavers are as the designs reflect the social hierarchies and stratification in society. Sri Lanka has a long history of weaving, but Lorna Deveraja in her research argues that Muslims were also skilled weavers who introduced the ‘salagama’ or ‘weaver’ caste to the island. “There’s evidence to show that during the Dutch period the Muslim weavers have been given preferential neighbourhood occupation and were one of the few communities allowed inside Colombo. When talking about weaving and lace, you have to talk about the Dutch and Portuguese influence on the lacework in the Rukada jackets of women. But when it comes to embroidery, something that you will observe in Rukada is that the nobler and higher you are in society, the more embroidery work becomes very intricate. The king’s costume is full of intricate designs and the same goes for the attire of women. But the village characters are clad in a simple waist cloth and a plain jacket. So from clothes, you can depict the social hierarchy and differences. But unfortunately, today what has happened with the puppeteer community is that there are only a few who know to do embroidery and it's costly. So what they have resorted to is replacing embroidery with cheap beads and sequins.”

De Mel also shed light on two types of Somana in Rukada – the Raja Somana and Mudliyar Somana. In the Ehelepola Saga, the Ehelepola Kumarihami displayed at the Munich Puppet Theatre Museum wears a foot-long, wrap cloth of white silk satin with more applications of red and green satin similar to a Malay cloth. In the early days, only the affluent could afford a Somana. “The Somana was worn by the Mudliyar, Kings and Queens but although the Somana was exclusive for these two groups, in Rukada people who occupied lower strata in society were seen wearing a Somana, for instance, the drummers. In my conversations with the community, when asked what would have been the reaction, they didn’t have an answer to that. But the way I see it is that it’s a form of protest.”

Rukada Natya today is not a lucrative business and the younger generation is moving away from this interesting and traditional art form. Even though much could be done to preserve the tradition, puppeteers remain to be a neglected segment of society and their voices are lesser heard today.

0 Comments