Apr 10 2018.

views 857Lighting is everything and photography means playing with light.”

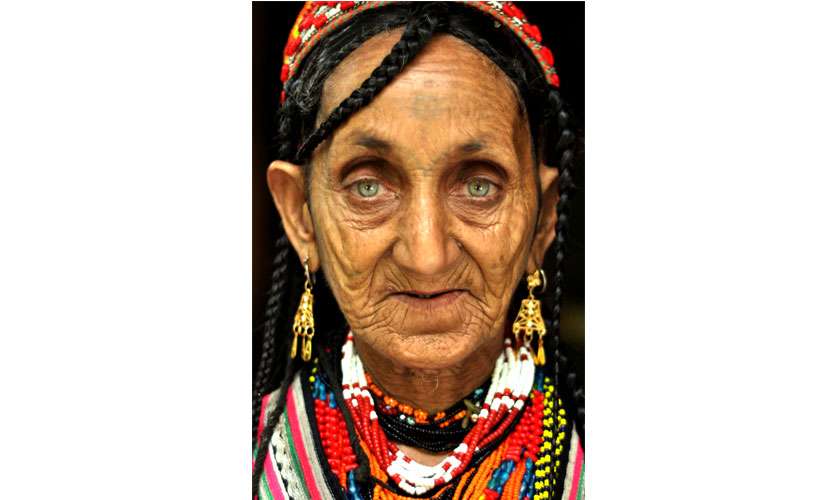

The purple pops of apricot blossoms in Gilgit-Baltistan, the azure blue of Kashmanja’s ice cave, and the penetrating eyes of a Wakhi child from the remote Chikar village are just some of the surrealistic charms echoing through the lens of Pakistani photojournalist, Mobeen Ansari. In an email interview, he chronicles the essence of travel photography and how it sparked off a profound interest in him.

Would you mind telling us when did you recognise photography as a language of expression?

This realization came at different points in my life. Both my grandparents did photography as a hobby when they were younger, and my father too for a long time. Looking at them taking pictures, as well as my uncle Tapu Javeri (who is a renowned fashion photographer) fascinated me when I was little.

I was and am an introvert and arts was always my passion, and the best way to really express myself, from a very young age. I was a student of Arts in high school and university.

Photography was something I did in parallel to this. Some 16 years ago when I was in the 8th grade, my father owned one of the first digital cameras that had just come out (a Kodak) and I used to take it with me to school nearly every day. I found true joy in this and the ability to express myself. It also made me somewhat a ‘golden boy’ in school, taking photos of my friends, teachers, and life in school for the monthly school magazine.

My first big break was covering concerts for the famous rock band Noori. This was a test of my skills and opened a lot of doors.

By the time I was in the first year of university I had mastered using a DSLR and would photograph college events. My college is in an old and interesting neighbourhood so I got to do a lot of street photography in my free time.

During summer vacations that year I got my first paid shoot and started doing it professionally by then.

Most of your photographs are affixed to getting one thing right — the religious plurality across Pakistan. How do you regard this statement?

I think this statement is more relevant to my newly released book ‘White in the Flag: A Promise Forgotten’, which is based on lives and festivities religious minorities of Pakistan. I believe that depicting religious plurality across Pakistan is just one aspect of my photographic work, as I also do travel photography and photojournalism in general.

We’re keen to know what your travel process was like for your books to happen. Did you just hop onto a bus and plan on journeying through sleepless nights?

Both books had entirely different game plan and trips, but very often I would do photography for both books on the same trip, to better utilize budget and time.

My first book ‘Dharkan: the Heartbeat of a Nation’, is about iconic people of Pakistan and it features their portraits and stories. This involved setting up appointments with different people and lining them up in a way I could do this set between three days to one week. Some subjects had to be approached personally and if I was lucky, those shoots would happen spontaneously. At times I would have a few hours notice and get on a bus right away.

My second book ‘White in the Flag’ is about religious minorities of Pakistan. For this I had to schedule photography around different festivals e.g. Christmas, Holi, Chowmos, etc.

On this note, when I go to North Pakistan it is an entirely different routine. I often visit Hunza to photograph autumn colours or apricot blossom. Autumn falls on the same dates (end of October to early November) and I plan it in a way that each district has different levels of autumn.

Apricot blossom is the other way round. It is more unpredictable and is subject to climate change. I had to postpone my trip by 3 weeks and when it was time to go, it snowed! But as soon as the snow melted in 24 hours the leaves started blossoming and my friends living there told me to be there quickly. It takes 15 hours to reach so I got in a car the same night and arrived on time!

You’re not only a photojournalist but also an active sculptor. Is there a connection between the two? If so, how do you balance labels?

That is the joy of being an artist, that you can choose to work with any medium. Academically, I’m not a trained photographer, but a fine artist. However studying painting, sculpture, miniature, and printmaking allowed me to give more depth to photography and create my own style.

I feel that there indeed is a strong connection between the two because sculpture allows me to understand light and texture on a face, while photography- especially portraits- allow me to understand faces and expressions. My sculptures are usually busts, pretty much the same ratio as my portraits which go from head to chest.

I don’t think there are any labels when it comes to being an artist with different mediums. Greats like Michelangelo, da Vinci, and others worked with different mediums. Jim Carrey is primarily an actor, but he is also an equally fantastic painter.

Whom would you consider your influences and why?

Having been a student of arts for almost all my life, I draw inspiration primarily from painters. Photographers are actually secondary inspirations.

Rembrandt is my most favourite. He had such a wonderful command of light that told stories about his subjects and did justice to every aspect of his subjects, down to age. For example his self-portraits in his youth had brighter colours and his last portraits were quite dimly lit- which reflected his circumstances in both times. I try to use Rembrandt’s lighting and also color in my portraits.

I’m also a fan of Glenn Brown, who recreates classic paintings and subjects in a quirky manner, often exploring texture using thick paint strokes. This helps me understand and plan the overlap between texture and lighting. I also like Salvador Dali as he effortlessly warped the world in his paintings and opened everything to the imagination.

From photographers, I love works by Eshter Bubley, Gregory Crewdson and Steve McCurry, all for different reasons.

Eshter captured beautiful and expressive photos of ordinary people in everyday lives and captured some of the most intimate moments I have ever seen. Her photos from 1940’s and 50’s take you back to that time. Seeing her photographs helped polish my own observation skills, to do street photography in Pakistan.

Gregory Crewdson created stories in everyday urban and home settings and staged his photographs in a very elaborate way. His ability to make something so great of frozen moments and his use of surreal light caught my eye,

Steve McCurry is my inspiration for portraits. A few people have often compared my work to his but I don’t think I deserve that honour!

You draw a sharp focus on portraits and door frames. In this context, is opening doors to other people an allegorical element by capturing diversity regardless of creed?

There is a very interesting way to put this.

Old doors fascinate me as they tell stories of people who have lived there for years and centuries, and about the time they belonged to. They have this ability to absorb light in a very interesting way, as portraits of older people do.

Portraits for me are basically landscapes of people. I yet need to properly incorporate both of the above!

What are some of your fondest memories having worked with the Kalash community?

There are so many! My time spent with the Kalash community is one of the most memorable ones in my life.

When I went to Kalash for the first time in 2012, I did some research and found portraits of some old Kalash women- out of them one seemed to appear quite often. Her name is Bibi Kai and she has been photographed by many photographers from around the world. She has the most incredible piercing green eyes and a face which told thousands of stories. I knew I had to photograph her.

I took a printout of her photo and upon reaching Kalash valley I showed it to the locals, who led me to her. She came out of her house and gave me a firm handshake. I was so intimidated by her presence that I couldn’t get myself to properly focus on her while taking her photographs. Fortunately, I was successful a few tries later.

Over the next few years, I continued to visit Kalash and made it a point to visit her also. The last time I met her was two years ago and she remembered me very well. Though we speak different languages, she has adopted me as a grandson. This would be my fondest memory.

The other was when I photographed Chowmos, the winter festival in Kalash. It is their most sacred festival and a friend from the community was kind to take me to the festivities and allow me to document it. One part of the ceremonies, Sarazari, is where the girls made a big fire (to earn blessings) and go door to door to collect dry fruits and sing prayers of prosperity for each individual residing there This goes on all night and involves going up and down steep hills. It was fun and challenging trying to catch up with everyone while holding a tripod and a heavy camera bag and in midst of snowfall!

Where do you draw the line between what you can photograph and what you can’t? Are there any situations when you swim the waters out of your comfort zone?

I always try to push my boundaries and limits to get the right shot. There are many such situations when I try to go out of my comfort zone. For example, I was in Gojal district (upper Hunza) for apricot blossom last year and wanted to photograph the pink apricot trees under the full moon.

In order to pull this off, I had to stay awake all night to wait for the moon to come up from the high peaks and head out in the freezing night. The temperature must’ve been about -15. This also involved in a dog chasing my student (a local living there) and myself! But I got the shot I was looking for.

Another incident is when I had gone to Mithi in Tharparkar district( which is in South Pakistan) to photograph Holi- the Hindu festival of colors. I wanted to get a riot of colours and really in the middle of it, so I went wherever there was most color being thrown around, exposing my camera, my hearing aids, everything! But it was worth it as I got to take one of my most favourite photos there.

I try to challenge myself equally while doing portraits.

I once had a shoot with Sana Mir, captain of the Pakistan women cricket team. She has a sense of strong leadership, grace,and strength. In order to depict these qualities, I photographed her under one of the arched gateways of Walled City in Lahore, called Delhi gate.

To get the right lighting and shadow and avoid the rush of people, we had to do this as early at 6 in the morning. Coordinating this then controlling light before sunlight would get harsh was quite a challenge, but I believe I was successful in getting the right shot.

After examining the way darkness took over space during your visit to a tomb in Lahore, what does ‘light’ mean to you?

My father once told me something very interesting about the painting ‘The Last Supper’ by Leonardo da Vinci.

In this painting, the use of light is very symbolic. Jesus is in the center, the light is on his back, but also emanating from within him, as a symbol of God’s source of enlightenment. The disciples who are furthest from him are darker in illumination, symbolizing the sins.The darkest point is Judas Iscariot, the one who will betray him a few hours later. Basically, this use of light told one whole story of the Bible.

Lighting is everything and photography means playing with light. Be it sunset light that falls on snow capped mountains, or be it soft light that falls on a subject’s portrait, it is the make or break factor that can do justice or injustice, and tell the story.

I started my photography career photographing concerts for a band called ‘Noori’. More often than not there were venues which were dimly lit and because the band members moved quite a lot, it was a good first-hand training to work in low lighting. I’ve also specialized in night photography, so I find a lot of joy in using low light. Having said this, the visit to Nur Jehan’s tombs was quite interesting (and scary!). There was absolutely no light at all so I asked my assistant to illuminate it using a mobile torch. I fumbled a bit with the light positioning to try and light it in a way I could do justice to it. However, in middle of this, a whole army of bats flew at us and we had to run!

We love your shots of Skardu! What have you to say to budding travellers on the aspects of travelling to areas slightly off the quotidian?

I encourage travellers to definitely visit areas off the beaten path. I’ve found incredible beauty in such places, and I’ve found history and culture to be in its original form in those areas, untouched by commercialism. I make it a point to visit such places often. Every year a few friends and I go on an expedition to an unknown- or less travelled pass or valley in North Pakistan. One of these adventures was through Broghil Valley and Darkot Pass, a region also known as a part of the famous Wakhan Corridor. For me, that place is every photographer’s heaven, from portraits to ever-changing landscapes. That said, Skardu isn’t exactly such a place but it is incredible, and I absolutely love going back to Katpana desert located there!

Pics courtesy: Mobeen Ansari

0 Comments