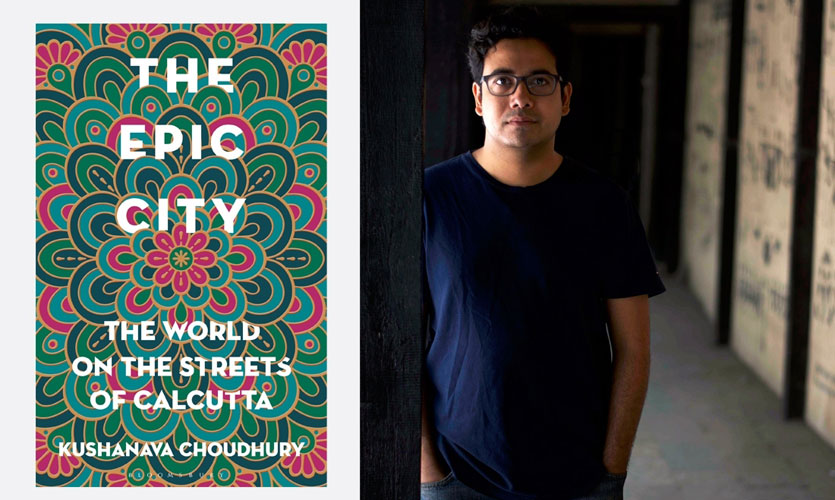

Indian American reporter and writer, Kaushanava Choudhury graduated from Princeton University and worked as a journalist for a leading English newspaper in Calcutta. His first book, The Epic City: The World on the Streets in Calcutta was released this year.

1. What got you into writing?

I'm not much good at sports, I can't sing and I can't play an instrument. I'm probably not as good a dancer as I like to think. Writing is all I got. I was putting together my own little magazines by the time I was 8 or 9 years old. I've been writing, one way or another, for as long as I can remember.

2. Tell us about your first book, The Epic City? What is the story behind it all?

The Epic City is the story of Calcutta in the 20th century, and of my fraught attachment to the city. There's an epic scale to Calcutta, which envelopes you and does not let you go. This book seeks to capture the totality of the overwhelming experience of Calcutta, where every detail - from the conversations at the local tea shop to the rallies of the then- ruling Communists, to the events that produced the partition of the subcontinent, are part of one narrative of the city, an all-encompassing narrative of epic scope.

I moved to the US from Calcutta when I was 12. But the city never let me go. I could never start over and pursue the "American Dream". The city drew me back. After graduating from Princeton, I went back to work as a newspaper reporter at The Statesman, the city's largest paper and that changed the trajectory of my life.

3. You worked as a reporter for an English newspaper in Calcutta. Did that play a huge role in your novel?

Yes, it played an enormous role. I worked at The Statesman, which was then the largest English paper in Calcutta, during the summer after my second year of college and then I came back from the US and worked there for two years after graduating from Princeton.

Eventually, I left Calcutta and went to the US for a Ph.D. but the city kept drawing me back. I felt like my real life was taking place there, and that graduate school was some kind of waiting room. I used to come back and stay in Calcutta for months at a time, visiting old haunts, hanging out on street corners, wandering the lanes like a vagabond. I was drawn back to the city by forces that I didn't fully understand or control. The city exercised such a magnetic pull over me that no matter where I went, in Johannesburg, in Istanbul, in Buenos Aires, I was always in search of other Calcuttas. That's why I finally wrote the book, to make sense of the city and my relationship to it.

The Epic City, which took many many years to write, was a way to make sense of this powerful attachment that Calcutta has over millions of people who have ever made the city their home.

The Epic City isn't a novel though, meaning it's not fiction. Everything in the novel, including all the characters and their dialogue, are true. Those are real people that I met and those are their words. I tried my best to make it read like a novel though, by imposing a narrative structure, to make a story out of all the people I met and the places I went, and my own memories of the city. That's where the writer's craft comes in, because real life doesn't follow any dramatic arc. It's just one damn thing after the other.

4. What is it about Calcutta that made you want to pick it as your subject for your first book?

I think that subject picked me rather than the other way around. I never had any great ambition to be a writer. Writing, rather, has always been the way that I've dealt with the tumult of my inner life. Some people pray; others do yoga. I write. For all my adolescence and adulthood, memories of Calcutta followed me wherever I went; They haunted every world I lived in. When that happens, you can either destroy your life, as many artists have done, or you can try to confront those ghosts. Writing The Epic City was my way to reach some kind of negotiated settlement with those phantoms that haunted me. I don’t think that art can save you, or redeem you, but it can sometimes give you some peace.

I'm 39 now, I've held jobs from time to time to pay the bills but I've never pursued a career in any field, trying to climb a ladder one notch at a time. What I've done instead, I realise now, is spend years sitting in little rooms, writing and rewriting, draft after draft, year after year, without an advance, or book contract, in spite of rejections from publishers and ample family pressure to do something more sensible. I say all this because everyone is a writer when they are 15 and fall in love for the first time and write poems or love letters to their beloved. Only a few, very obsessive kind of people remain stuck as writers, in a kind of arrested development. We never grow out of it to become something else.

5. What are some of your writing influences?

Syed Mujtaba Ali, Bohumil Hrabal, Phillip Roth, Junot Diaz, Roberto Arlt.

Roth and Diaz because they are the gurus of what I think of as the New Jersey school of American literature, to which I also belong. Syed Mujtaba Ali, because he was the master of the adda mode of writing, a polyglot and pandit whose greatest vice was that he was not boring enough to be respected as a difficult writer. Bohumil Hrabal because he wrote the history of the 20th century in picaresque form. He is such a seductively entertaining writer, like Mark Twain, that you almost never realise that his version of our times is truer than that of a hundred apparatchik historians. Roberto Arlt, because nobody knew how to bring the world of the street into literature (or journalism) like him, except maybe Truffaut in 400 Blows, if we're counting films.

I will never be as good as any of them even if I write for another 50 years, but these are a few who I learned a lot from while writing this book.

If we are counting movies, then Ritwik Ghatak's films had an enormous influence on me, because they tell the true story of Bengal in the 20th century. Only Ritwik seemed to understand the centrality of Partition at an existential level for Bengal. Everyone else seemed to treat it like an event, a calamity that happened at one point, like an earthquake or a flood, and then stopped, and from which we recovered, as people recover after a flood or an earthquake. Ritwik understood Partition in terms of the breakdown of the self. His films are about the collective unconscious of Bengal. He was very intentional about this in his films, as he writes in his essays on filmmaking. If we don't fully understand his films, then it's because we don't yet understand anything about what Partition wrought, what it continues to wreak upon us. Because Partition never ended. It's still going on. Maybe in another hundred years, we'll understand it; then Ritwik's films will be invaluable.

6. Tell us a little about your writing style?

I write in American. The language I use, its sensibilities and cadences, come from the way I spoke growing up in New Jersey. I think it's a blessing that I moved to America at a young age, because my relationship to the English language is totally different from what it is for most South Asian writers.

I live in India now, but I try to avoid speaking English unless absolutely necessary. I'll speak Bengali, Hindi, my broken Malayalam, anything but English if I can get by. Because English is not a language you ever hear in a tea shop in India. It's the language that rich people use when they're in the backseat of their chauffeur-driven cars, making nasty remarks about the driver while he is within earshot. English in India is a language used to exclude others and to assert power, so the English language in India invariably sounds like a language of command. That makes it hard to use as a literary language.

In America, as my father likes to say, even the sweepers speak English. The American language is much closer to the street, to everyday life, to jokes and adda, to a democratic popular culture. It has a much wider range than the English used in India (or, I suspect, in England). That's why Indian poets like Arun Kolatkar or Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, when they translated the populist Indian medieval Bhakti poets like Kabir and Tukaram didn't use Indian English - they drew on Bessie Smith, the blues and jazz; they used the American idiom.

7. Are there any plans for another book?

I'm writing a novel about murderers and shamans in Connecticut. It's about race cleansing, American amnesia and the ghosts of the past.

I've also been living in Cochin, Kerala for the past year doing research for a book about how the world - politics, religion, time, space - looks from the shores of the Indian Ocean in this part of the world. It's a very different view of human history than the one you get from Europe, North America, or, for that matter, from the blood-soaked plains of North India.

The Fairway Galle Literary Festival (FGLF) returns for its ninth year at the Galle Fort from 24 – 28 January 2018. For more information about the 2018 Festival visit galleliteraryfestival.com/

Read the interviews with the other authors here:

0 Comments